Home » Special Exhibits » Views on the Southwest » J.R. Willis Murals

Views on the Southwest

J.R. Willis Murals

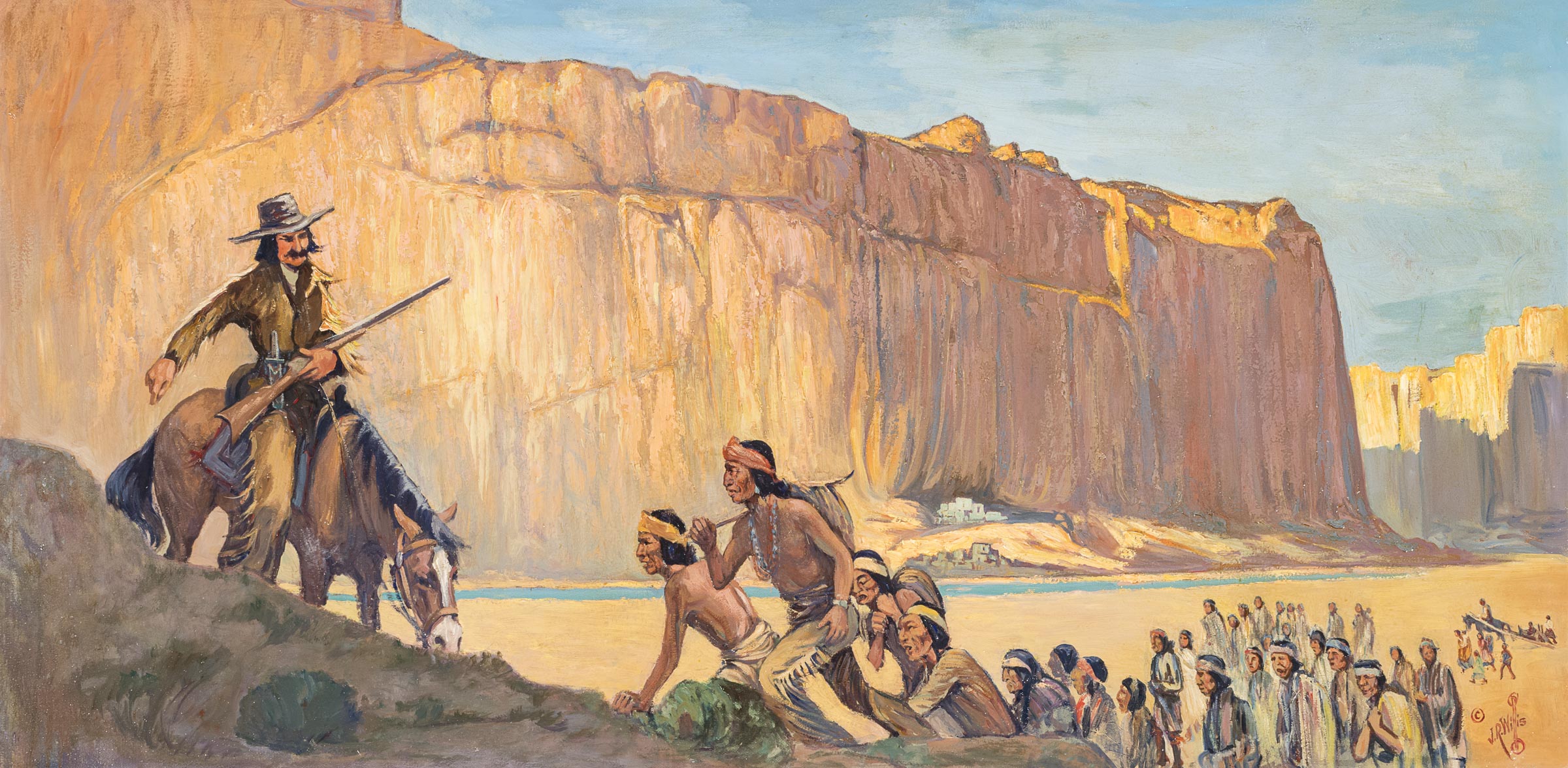

Cultural Crossroads & Conflicts

For thousands of years, the region that is now New Mexico has been a crossroads. From early trade networks of Native Americans, to the arrival of the Spanish in the 1500s, to tourist train travel in the 20th century, people and cultures continue to intermingle and coexist today. These convergences of people and cultures, however, have been rife with complex layers of history and conflict.

Read More

Joseph Roy (J. R.) Willis’s (1876–1960) series of murals, hanging in the Gallup High School library, depicts various scenes from the Spanish colonization of New Mexico (historical episodes depicted date from 1527 to 1605), the Mexican-American War (1846–48), and the Long Walk of the Navajo (1863–1866). Many of these historical encounters were violent, and Western American artists like Willis often depicted such events from an Anglo perspective.

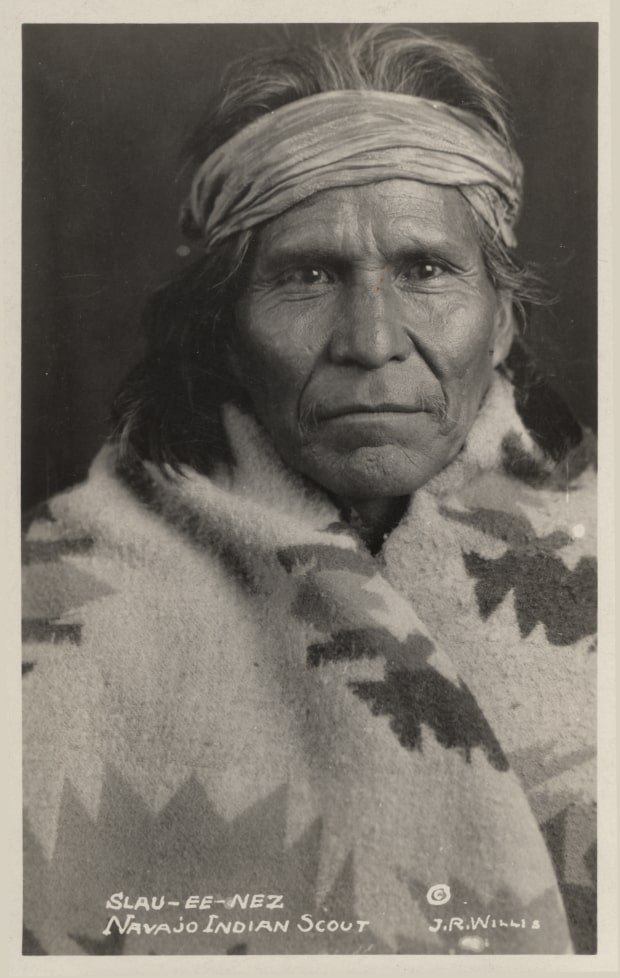

From 1917 to 1931, Willis lived in Gallup, where he ran a photography studio and curio shop and explored nearby reservations with camera in hand. These photographs served as visual references for his paintings, and some became postcards. Prior to his extended stay in New Mexico, Willis had worked as a newspaper reporter, cartoonist, and illustrator, and had even painted backdrops for Universal Studios in California. Perhaps this last experience influenced the “cinematic” feel of his canvases, with their panoramic format, theatrical staging of figures, and dramatic lighting.

Times have changed since these murals made their debut at the high school, and today, other murals created under the New Deal are now facing potential removal because some see their depiction of Native Americans and Hispanic people as racist and as reinforcing historical stereotypes and oppressions [explore more here and here].

The murals were commissioned by the Gallup McKinley County Schools “with the purpose of assisting in the teaching of history.” As you peruse these seven murals and the stories they tell, whose version of history do they tell, and what artistic choices did Willis make to tell it?

Explore artistic responses to these works with contemporary Diné painter Clint Holtsoi and Laguna potter, educator, and historian Teri Fraizer.

5.

Untitled (Juan de Oñate at El Morro)

Click to view Teri Fraizer’s Guest-Curated Tour responding to the murals’ depiction of Spanish colonization.

Click the icon that best captures how you are feeling about the history and discussion of Western American art presented in this exhibit.