The artists represented in Gallup’s New Deal art collection reflect the whole of American society, which banded together under the New Deal to ensure the country’s future. The collection includes works by European-born artists, artists from the East and West coasts and middle of the country, Native American and Hispano artists, male and female artists, twenty-something emerging artists and older, established artists, and both academically trained and self-taught artists.

This disparate group constituted an evolving multilayered and interconnected professional network prior to the New Deal. In the first three decades of the 20th century, New Mexico was a small-population state made up of small communities (in 1930, Taos had roughly 2,000 people, Santa Fe 11,000, and Albuquerque the most at 27,000). In 1940, Gallup’s population was about 7,000. The artist community was also small in the sense of being highly networked: artists attended the same schools, trained together, belonged to the same artist fraternities and organizations, lived as neighbors, painted together, and, of course, exhibited together.

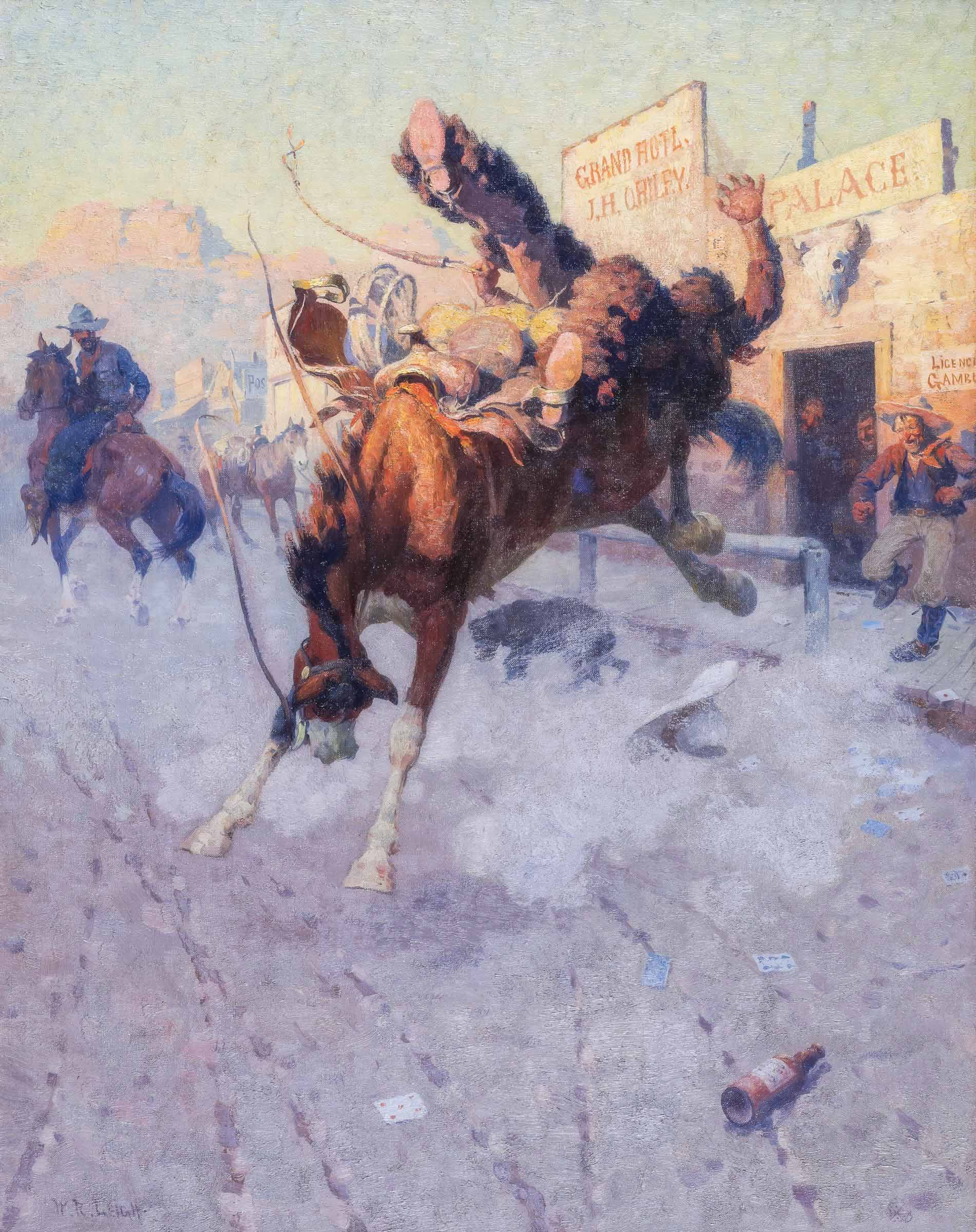

Horses and Whiskey Don’t Mix

by William Robinson Leigh

A handful of artists represented in Gallup’s New Deal art collection are part of the initial wave of Western American artists who first ventured west in the 1800s and 1900s, and who would continue to visit from their East Coast studios over the course of their careers. Albert Lorey Groll and Elbridge Ayer (E. A.) Burbank accompanied anthropologists on trips to document what was largely viewed as a “vanishing race” of Native American peoples. Other artists, including William Robinson Leigh and Edgar Alwin Payne, were drawn west by commissions from the railroads to create promotional materials.

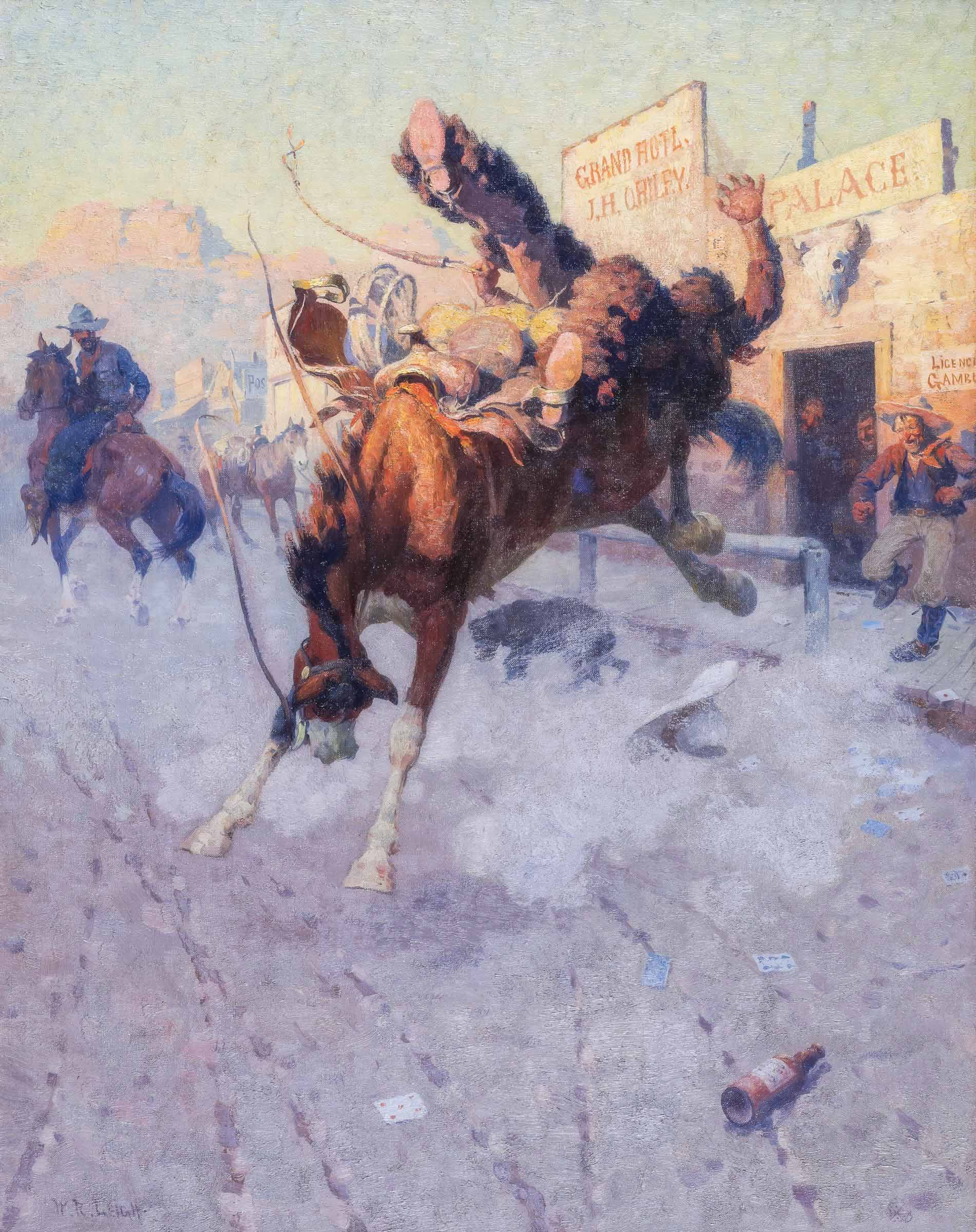

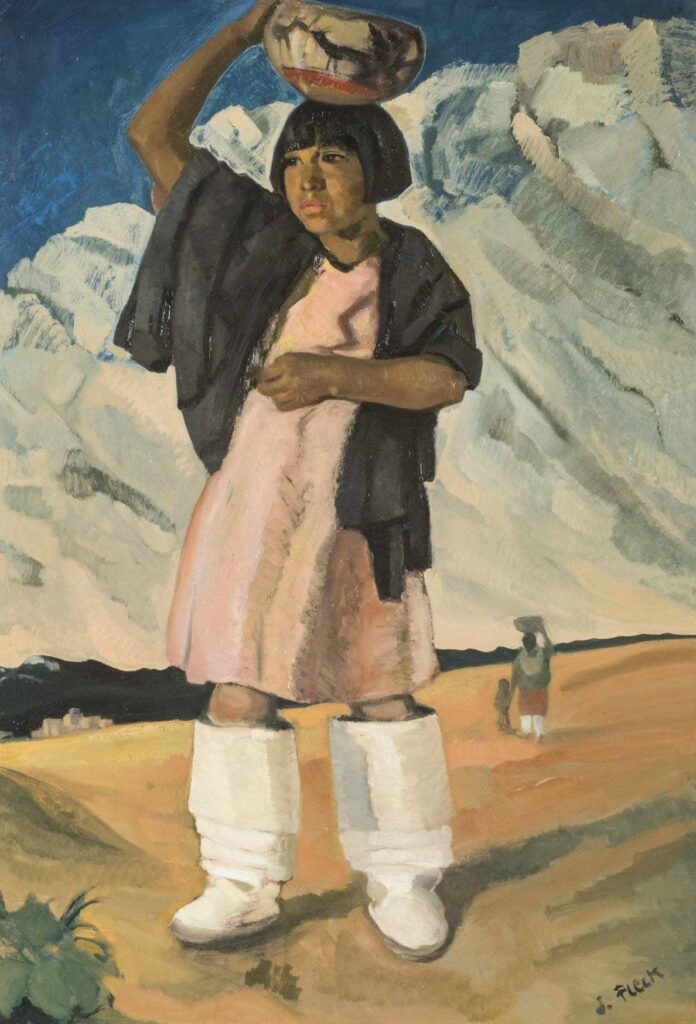

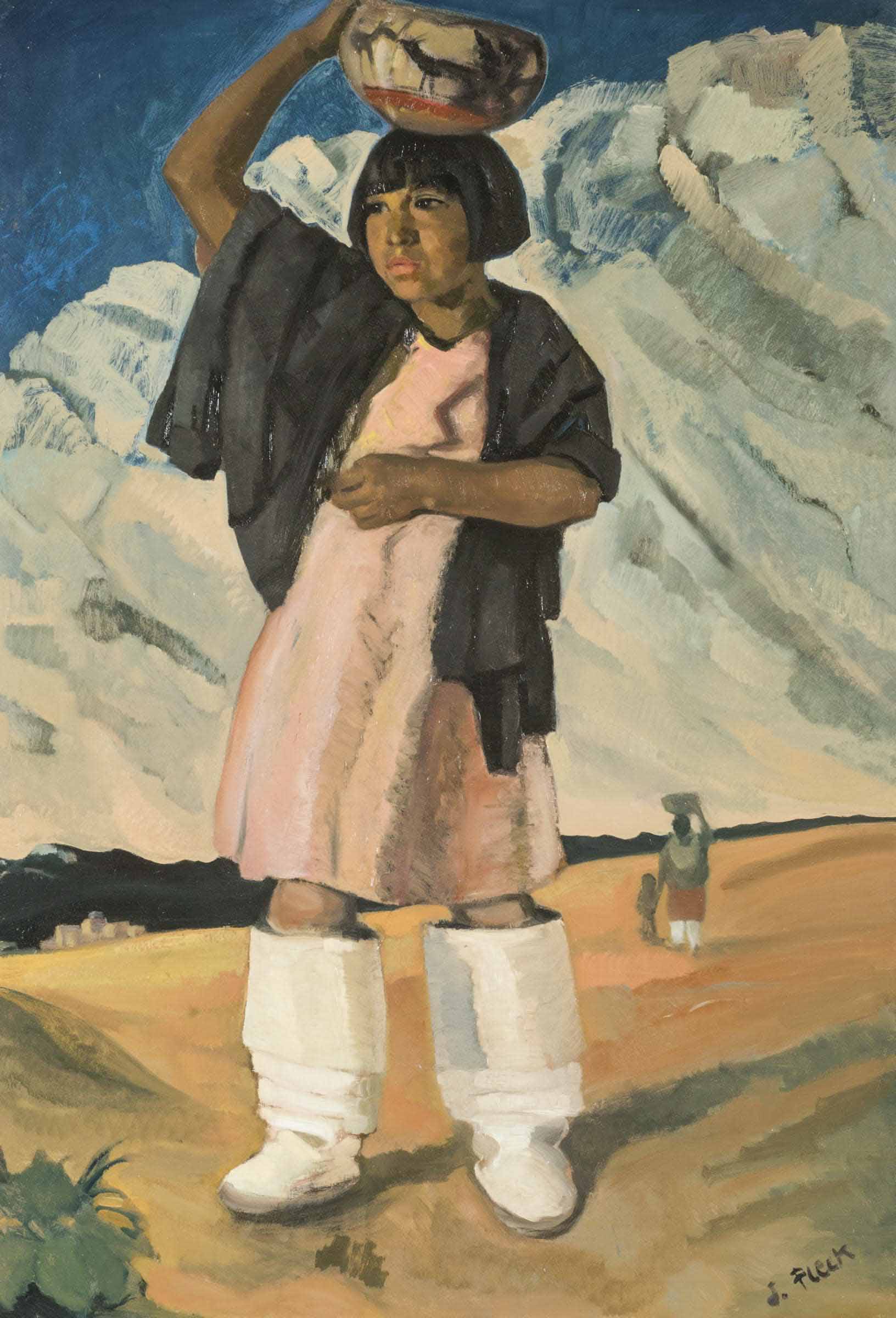

West Wind

by Joseph Fleck

In the first decades of the 20th century, a small group of painters established the Taos Society of Artists, an exclusive organization that played a foundational role in the creation of the Taos artist colony and institutionalized a traditional, representational style of Southwestern art focused on Native American subjects. Groll became an associate member. Other artists who moved in the Society’s orbit include Taos residents Gene Kloss and Joseph Fleck, stylistic adherents such as Herbert Tschudy, students of Society members such as Paul Lantz, and admirers such as J. R. Willis.

Cottonwoods

by Józef Bakoś

Meanwhile, the Santa Fe arts colony was pioneering a different path, one which appealed to modernists such as Józef Bakoś, who spearheaded the colony’s first official counterpart (and counterpoint) to the Taos Society, Los Cinco Pintores, in 1921. Perhaps no artist better encapsulates this era of New Mexico and American art history than Sheldon Parsons. Parsons’s art constantly challenged the line between realism and modernism, as did his career.

Through the 1920s, modernism picked up steam. In Santa Fe and Albuquerque, a local, stylistically idiosyncratic movement of younger artists took center stage. These included art-world rebel Brooks Willis; Lloyd Moylan, a persistent advocate for experimentation; Anna Keener Wilton, whose work also spans the spectrum of modernist theories and approaches; D. Paul Jones, known during his time as a contemporary landscape artist; standout pastelist Helmuth Naumer; and pioneering printmaker Louie Ewing.

Untitled (Taking Down a Finished Rug)

by Harrison Begay

Most of the Native artists represented in Gallup’s New Deal art collection, including Allan Houser, Harrison Begay, and Timothy Begay, got their starts as students at the Santa Fe Indian School in the first half of the 1930s, just as New Deal art programs were taking root in New Mexico. In 1932, non-Native art teacher Dorothy Dunn established The Studio School at the Santa Fe Indian School and institutionalized a primitivist stylistic methodology that took root within Native art education and reverberated through the Native art market. Jose Rey Toledo received instruction in what became known as the Studio Style at the Albuquerque Indian School. The Studio Style is characterized by a flat, linear aesthetic and focus on “traditional culture” as subject matter. It was incredibly successful commercially and came to define “Indian art” for generations to come. As such, it was fully embraced by the New Deal.

Trastero

by Uncredited Hispano Artist(s)

The New Deal perpetuated efforts to preserve “traditional” Nuevomexicano art that had been underway since the mid-1920s. In collaboration with State vocational schools, New Mexico’s Federal Art Project (FAP) established workshops to produce Spanish Colonial–style furniture and decorative arts. Elidio Gonzales trained at the Taos Vocational School and likely produced a number of furniture pieces for the historic McKinley County Courthouse. The New Mexico FAP also commissioned the Portfolio of Spanish Colonial Design, fifty woodcut prints of New Mexico subjects colored in by artists. Eliseo Rodriguez was a young artist employed by the New Mexico FAP, and, among his other contributions, he hand-colored printed plates for the Portfolio. Rodriguez was then encouraged to learn the “dying” art of straw appliqué, which he and his wife, Paula, are credited with saving and reviving. The couple was named National Heritage Fellows in 2004 for this work.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get GNDA updates

Gallup and McKinley County are situated on the ancestral and current homelands of the Diné and Ashiwi peoples.

Gallup’s New Deal art collection consists of over 120 objects created, purchased, or donated from 1933 to 1942 through New Deal federal art programs administered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to support artists during the Great Depression.

The Gallup New Deal Art Virtual Museum features three types of exhibits, combining traditional and non-traditional approaches to illuminate academic, creative, and individual understandings.

Gallup’s New Deal art collection includes works by a demographically, professionally, and stylistically diverse group of named and unnamed artists.

Image Use Notice: Images of Gallup’s New Deal artworks are available to be used for educational purposes only. Non-collection images are subject to specific restrictions and identified by a © icon. Hover over the icon for copyright info. Read more