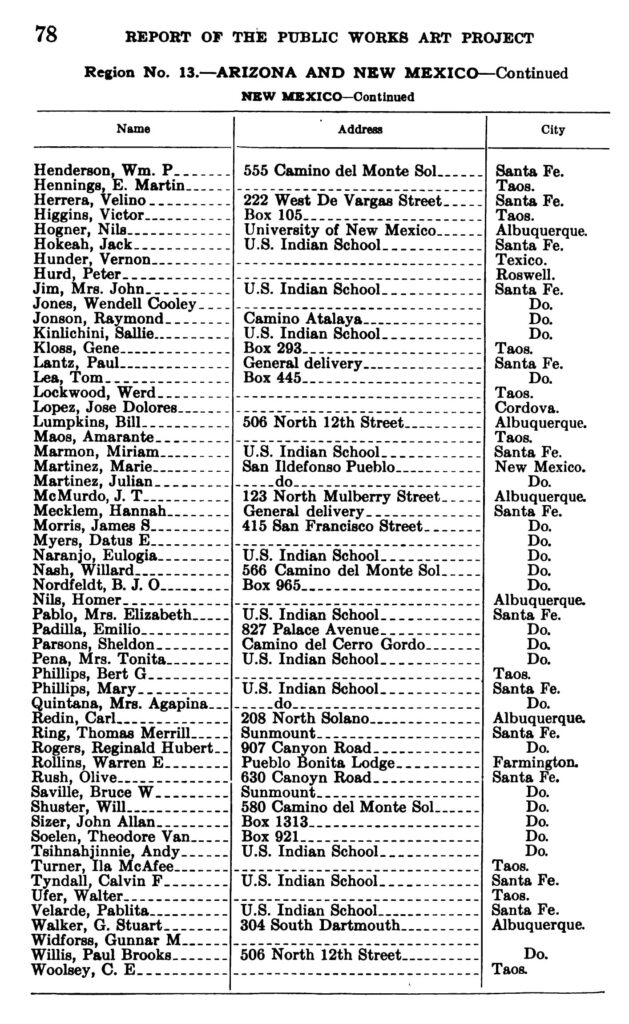

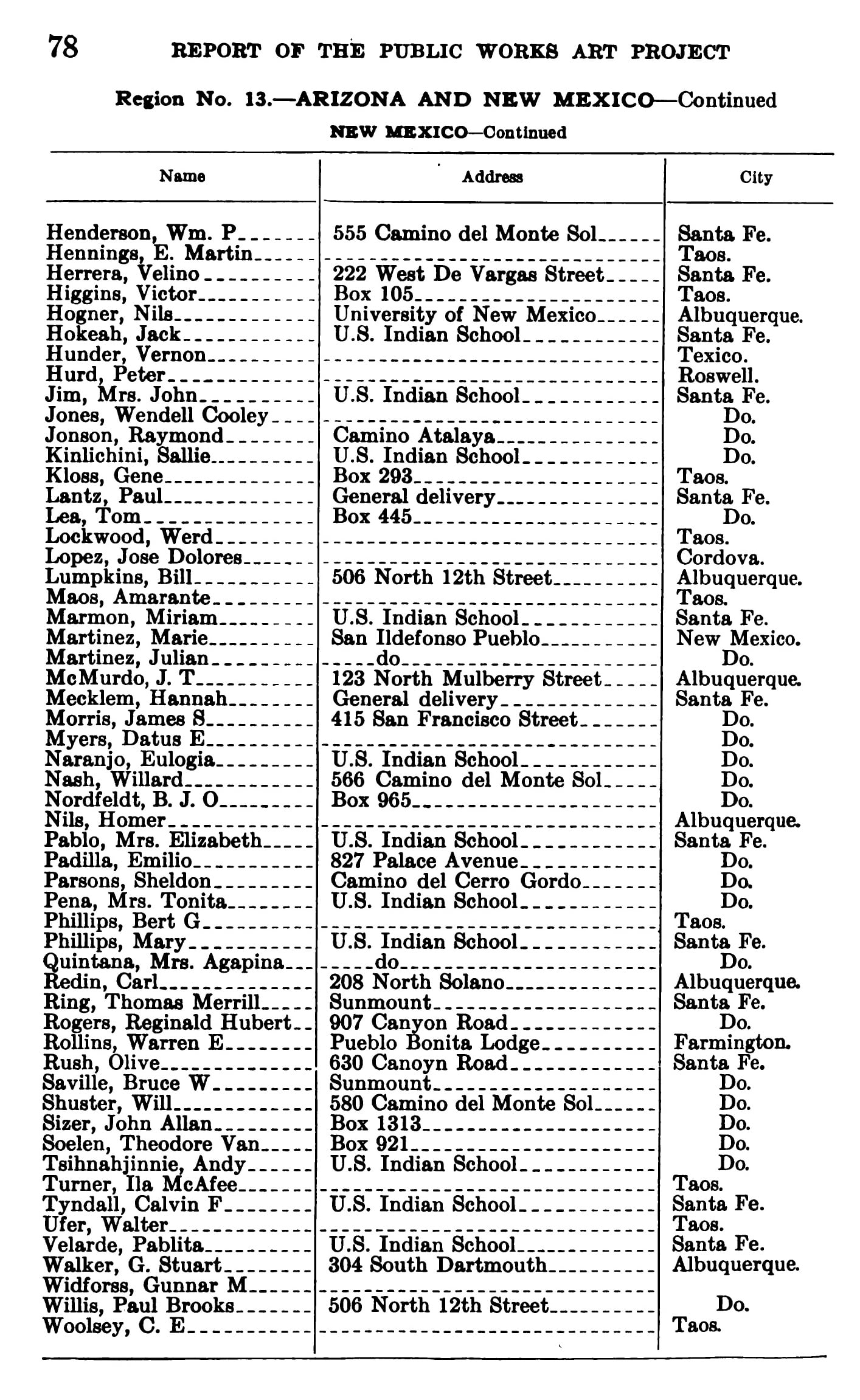

Partial list of New Mexico artists employed by the New Deal’s Public Works of Art Project (page 78 of the 1934 “Report of the Public Works of Art Project”).

The PWAP employed in-need professional artists at different levels, proving the concept of “artists as workers.”

The first federal program to support artists, the Public Works of Art Project (1933–1934), used newspaper advertisements to solicit participating artists from across the country. Applicants had to prove they were professional artists and had to pass a needs test. Once hired, they were classified as “Level One,” “Level Two,” or “Laborer.” This ensured that a broad spectrum of artists was supported, but also meant that they received different salaries. Still, PWAP artists were paid an average of $34 per week (about $800 in today’s money – a decent salary).3

PWAP Director Edward Bruce summarized the Project as “a recognition of the value of culture and the arts in American life. It is the first completely democratic art movement in history. A great republic has accepted the artist as a useful member of society and his work as a valuable asset to the State.”4 Overall, the PWAP employed more than 3,500 artists who created over 15,000 works of art.

Michigan artist Alfred Castagne sketching WPA construction workers (May 19, 1939).

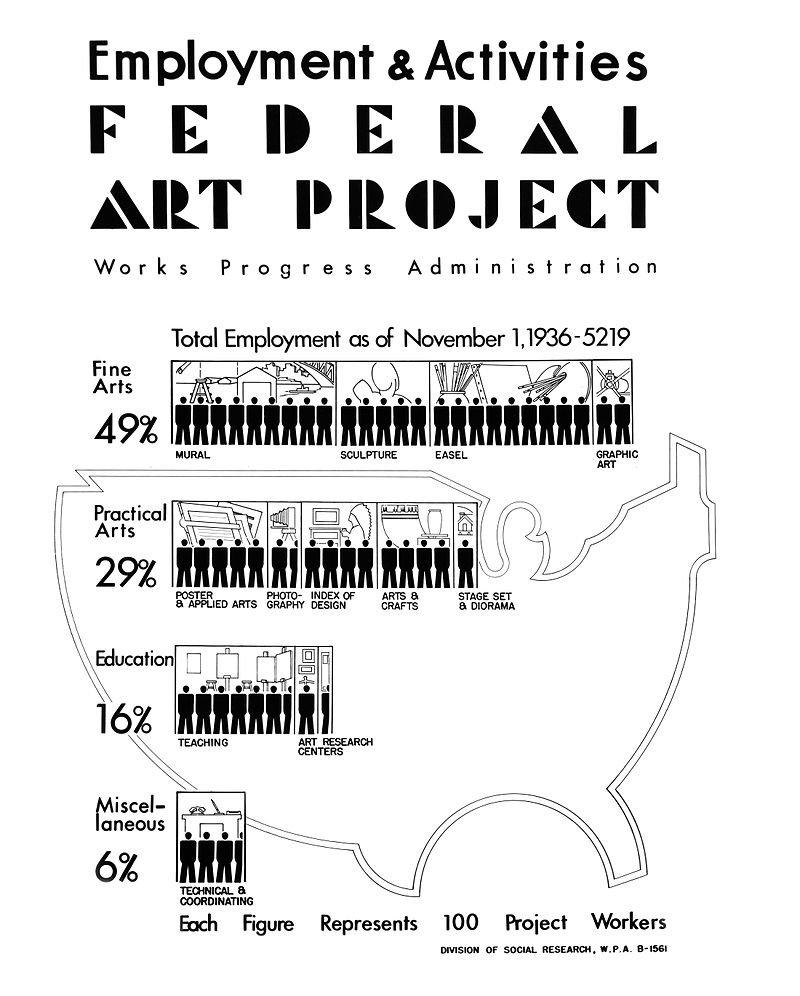

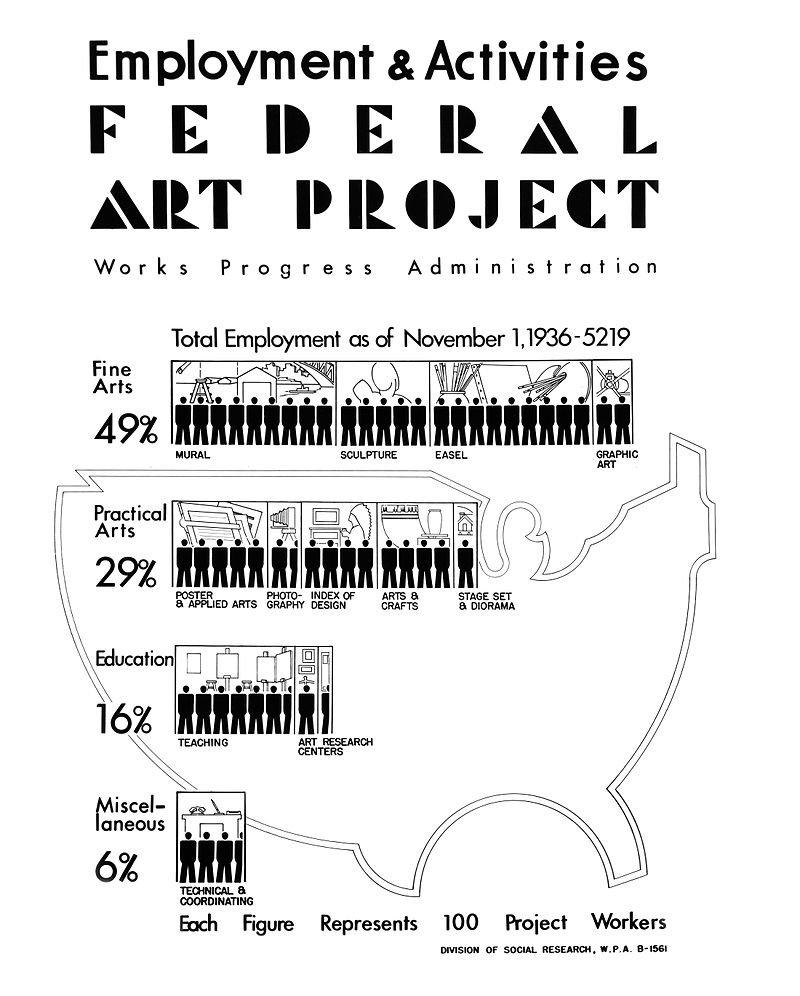

The FAP provided work relief to artists from a variety of backgrounds while also perpetuating racial and class biases.

The PWAP, which only lasted five months, proved the concept that artists could be held to the same standards of production and provide the same public value as other governmentally employed laborers, such as construction workers. The New Deal’s signature artist relief program, the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, or FAP (1935–1943; renamed WPA Arts Program in 1939), picked up where the PWAP left off as a fully relief-oriented program.

The FAP was created to “to provide work relief for artists in various media—painters, sculptors, muralists, and graphic artists, with various levels of experience.”5 Its emphasis on providing relief distinguishes the FAP from a concurrent federal arts program run by the Department of the Treasury—the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture (1934–1943; renamed the Section of Fine Arts in 1939). The Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture focused on supporting artistic excellence, regardless of need, by engaging artists through competition and by invitation. In contrast, FAP Director Holger Cahill stated that “the organization of the Project has proceeded on the principle that it is not the solitary genius but a sound general movement which maintains art as a vital, functioning part of any cultural scheme. Art is not a matter of rare, occasional masterpieces.”6

In broad strokes, the FAP perpetuated a socioeconomically and racially biased distinction between “fine artists” and “craftspeople” and employed artists differently along those lines. Formally trained artists (mostly white, male artists) were retained for the mural, easel, sculpture, and graphic art divisions of the program and employed as salaried professionals, expected to fulfill a quota (creating a certain number of original artworks within a certain timeframe) or to complete public art projects such as murals. Artists without formal training and/or working in “craft” traditions and “folk” arts (including many artists of color and female artists) were relegated to the arts education and technical divisions. In New Mexico, artists categorized as “craftspeople” were often employed in workshops to produce furniture and decorative arts in bulk. (Learn more about how New Mexico’s New Deal arts workshops functioned in the New Deal Nuevomexicano & Decorative Arts Special Exhibit.)

The basic wage of FAP artist-workers was $23.60 per week7 (about $500 in today’s money)—a notable reduction from the PWAP, perhaps due to the expansion of employment opportunities beyond professional artists. The Federal Art Project put more than 10,000 artists to work across the country and produced hundreds of thousands of artworks.

“Employment and Activities” FAP poster, dated November 1, 1936.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get GNDA updates

Gallup and McKinley County are situated on the ancestral and current homelands of the Diné and Ashiwi peoples.

Gallup’s New Deal art collection consists of over 120 objects created, purchased, or donated from 1933 to 1942 through New Deal federal art programs administered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to support artists during the Great Depression.

The Gallup New Deal Art Virtual Museum features three types of exhibits, combining traditional and non-traditional approaches to illuminate academic, creative, and individual understandings.

Gallup’s New Deal art collection includes works by a demographically, professionally, and stylistically diverse group of named and unnamed artists.

Image Use Notice: Images of Gallup’s New Deal artworks are available to be used for educational purposes only. Non-collection images are subject to specific restrictions and identified by a © icon. Hover over the icon for copyright info. Read more