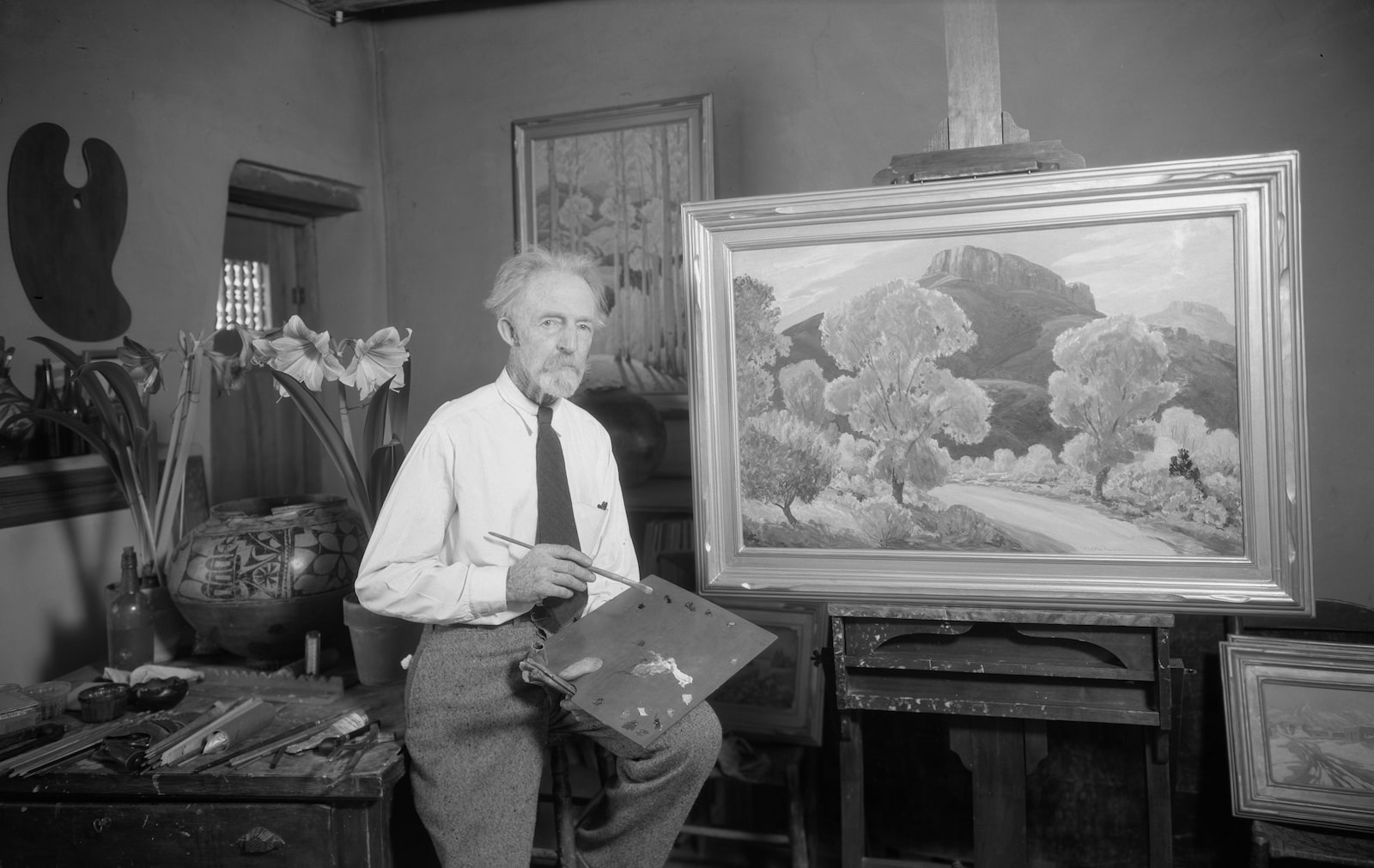

It is largely by serendipity that Sheldon Parsons became a painter of the New Mexico landscape. A student of noted artist William Merritt Chase at the National Academy of Design, Parsons was enjoying a career as a successful New York City portraitist in the early 1900s. President William McKinley and Susan B. Anthony were two of the famous Americans whose likenesses he painted. However, his career and life trajectory abruptly changed upon the death of his wife in 1913. Parsons sold everything and headed west with his twelve-year-old daughter to complete a mural commission in San Francisco. Parsons suffered a relapse of tuberculosis in Denver, and, on the advice of doctors, the duo changed course to head south to the curative climate of New Mexico.

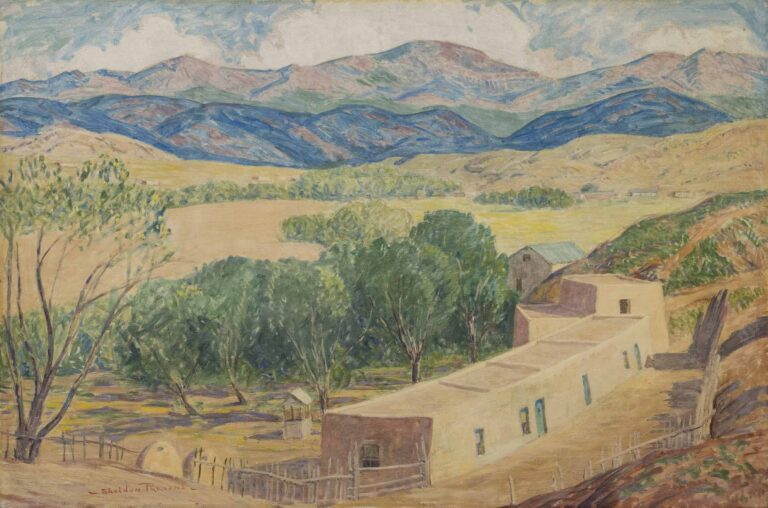

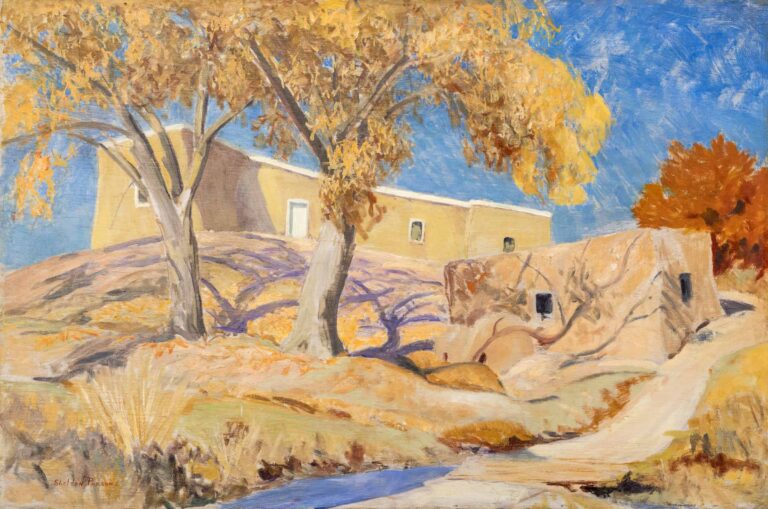

Parsons settled in Santa Fe and, absorbed by the color and light of his new surroundings, began to paint landscapes saturated with the blue, red, and golden hues of the Southwest. He immediately made an impression in the budding artists’ colony, and his paintings quickly became “one of the chief attractions at the state museum in Santa Fe [the Museum of New Mexico].”1 At the same time, Parsons continued to show in New York City as a member of the prestigious Salmagundi Club, and his work was also exhibited across the country from Chicago to Oklahoma to Washington, DC. In 1914 and 1916, Parsons completed commissions from the Santa Fe Railroad for two paintings of the Grand Canyon. Within a year of its 1917 opening, the Museum of New Mexico Art Gallery (now the New Mexico Museum of Art) arranged a “permanent Parsons gallery . . . which [was] hung with 22 of his most representative canvases.”2

Parsons was a key figure in consolidating the efforts and cementing reputations of the Taos and Santa Fe art colonies. From the time he moved to Santa Fe, Parsons supported the Museum of New Mexico. In 1915, he organized an exhibition of Taos artists that was described thusly: “never before in its history has the southwest seen so great or so typically an American art exhibit.”3 By 1920, Parsons was appointed “curator of art exhibits” for the museum’s Art Gallery, a post he held for two years.

As curator, he engaged in the burgeoning debate over the new modernist movement. Parsons himself tended toward a more realist approach in his work. Though he was denied membership in 1923 to the academically inclined Taos Society of Artists, he remained informally affiliated with the group, spending a lot of time painting in Taos—and his daughter married Taos Society artist Victor Higgins in 1919. Yet Parsons remained open-minded. Contemporary critics noted changes in his approach—a move toward bold colors and “freedom . . . in handling”4—as he exhibited frequently in Santa Fe in the teens. After assuming the position of art museum curator, Parsons defended modernism, writing that “this movement in modern art is too great, too universal a movement, for there not to be some grain of truth at its heart and doubt begets humility and humility begets wisdom.”5 He then rearranged the Southwestern art exhibit at the museum, provoking praise from some and criticism from others. Parsons dismissed his critics as “illiterates applauding with their mouths”6 in a letter to the editor of the Santa Fe New Mexican. Yet the political overtones of the debate—several modernist artists were staunch leftists, and the artistic community generally tended toward a “bohemian” outlook at odds with Santa Fe’s conservative political leadership—ultimately cost Parsons his job. He was fired to appease tensions between the museum and civic leaders.

Another notable achievement of Parsons’s as curator was to arrange a “loan art exhibit” of one hundred works from private collections in Santa Fe, the first of its kind. Parsons also helped to organize the Santa Fe Arts Club in 1921, which some scholars mark as the official beginning of the Santa Fe art colony.7

Over the next decade, Parsons continued to evolve, increasingly edging on modernism. Yet by the mid-1930s, as “radical” movements such as Transcendentalism gained a foothold and younger artists took charge of the Santa Fe art colony, Parsons’s work began to look “conservative, with Parsons himself being relegated to the ‘old guard.’”8 In 1938, one critic referred to him as the “dean of New Mexico landscape painters.”9 Though Parsons died in 1943, his work continued to be a staple of the Santa Fe art scene and museum exhibits.