Louie Ewing is best known as a pioneer of silkscreen printmaking in the United States, a reputation he earned as a New Deal artist. Ewing moved to California in 1933, where he studied art at a junior college. He followed one of his instructors to Santa Fe, NM, in 1935, and almost immediately started working for the state’s Federal Art Project (FAP).

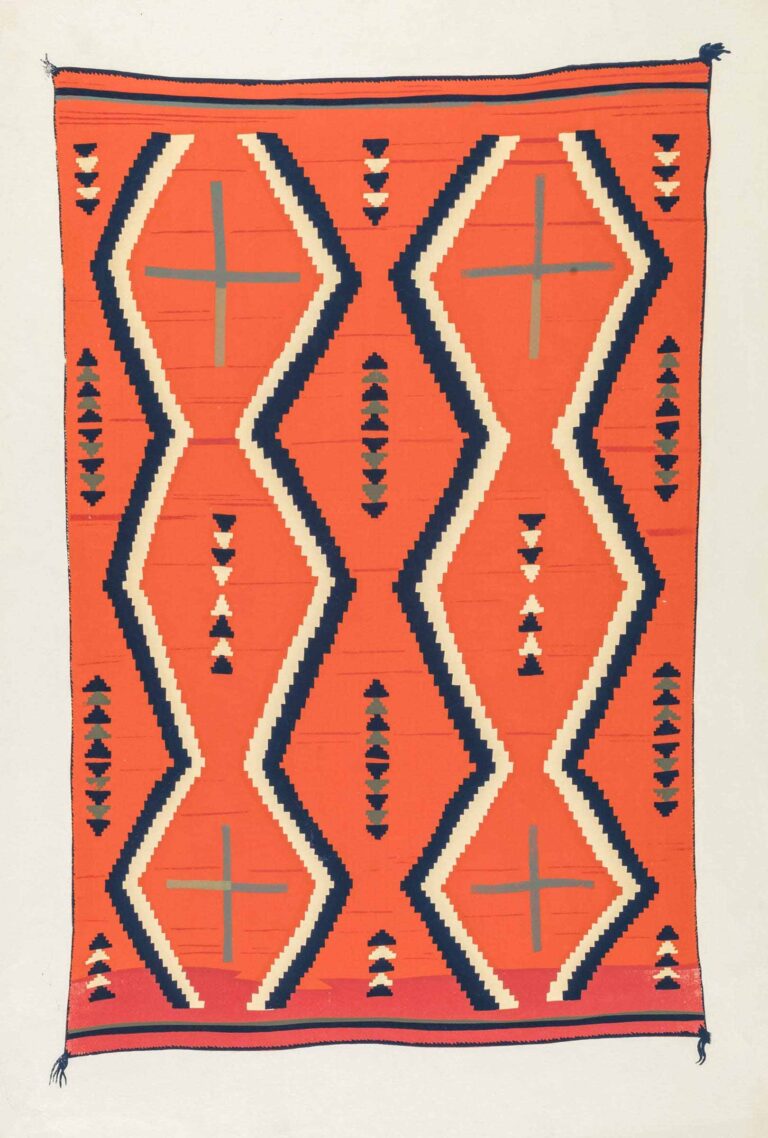

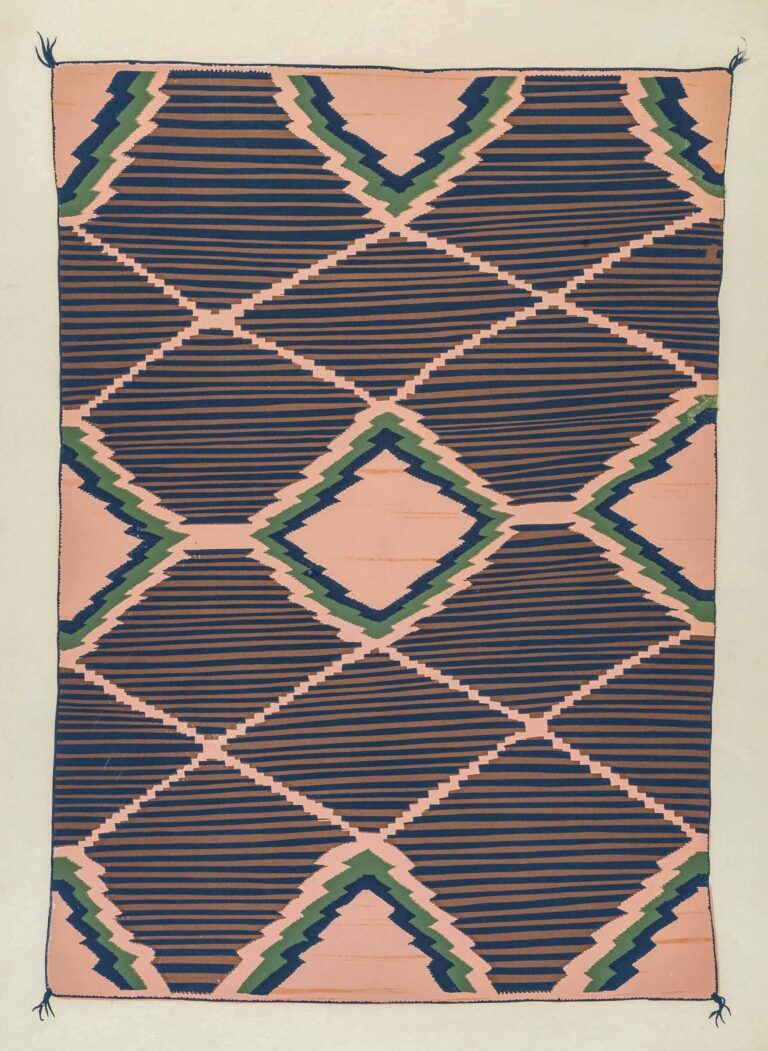

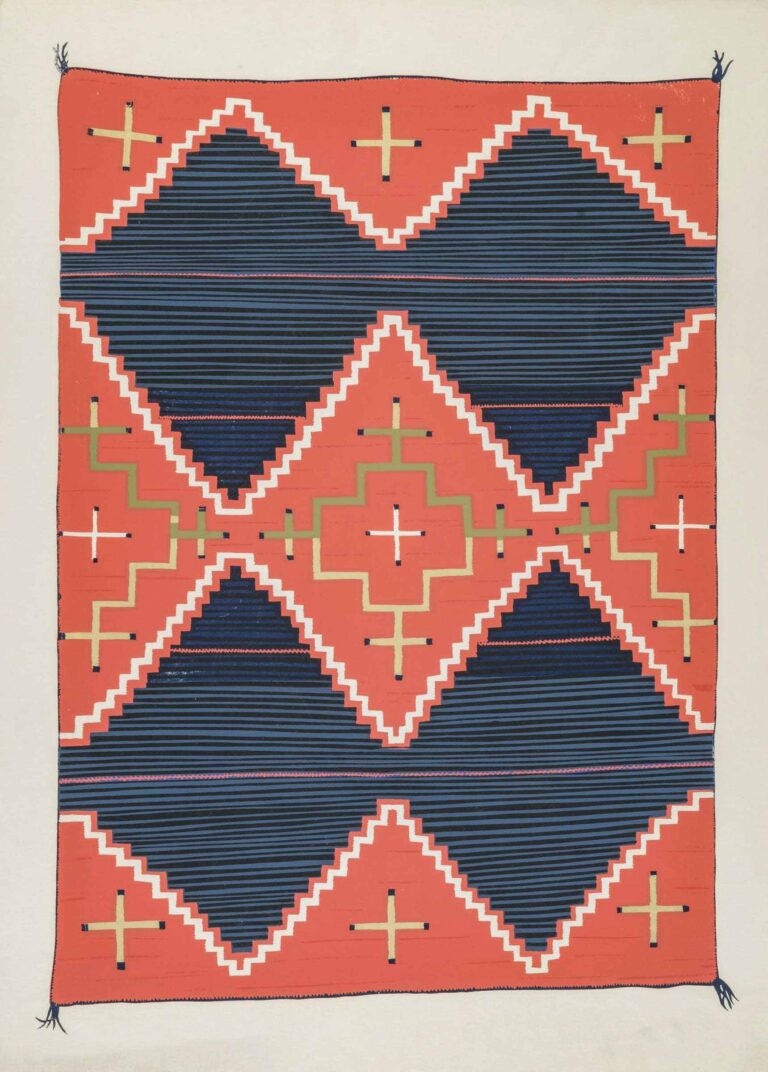

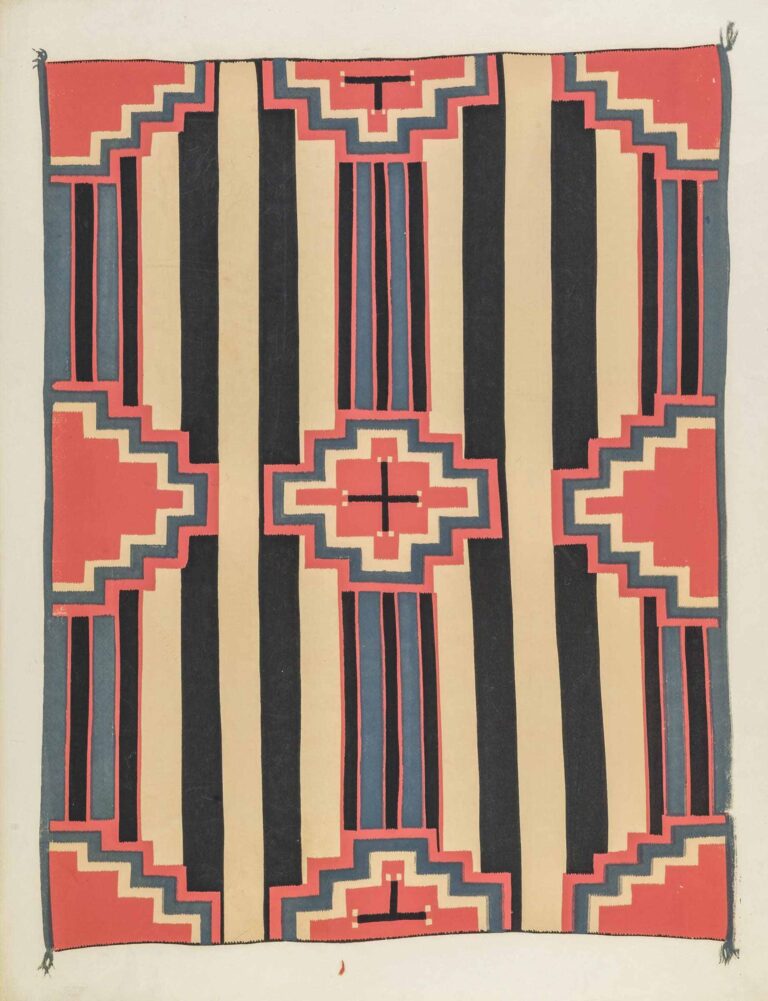

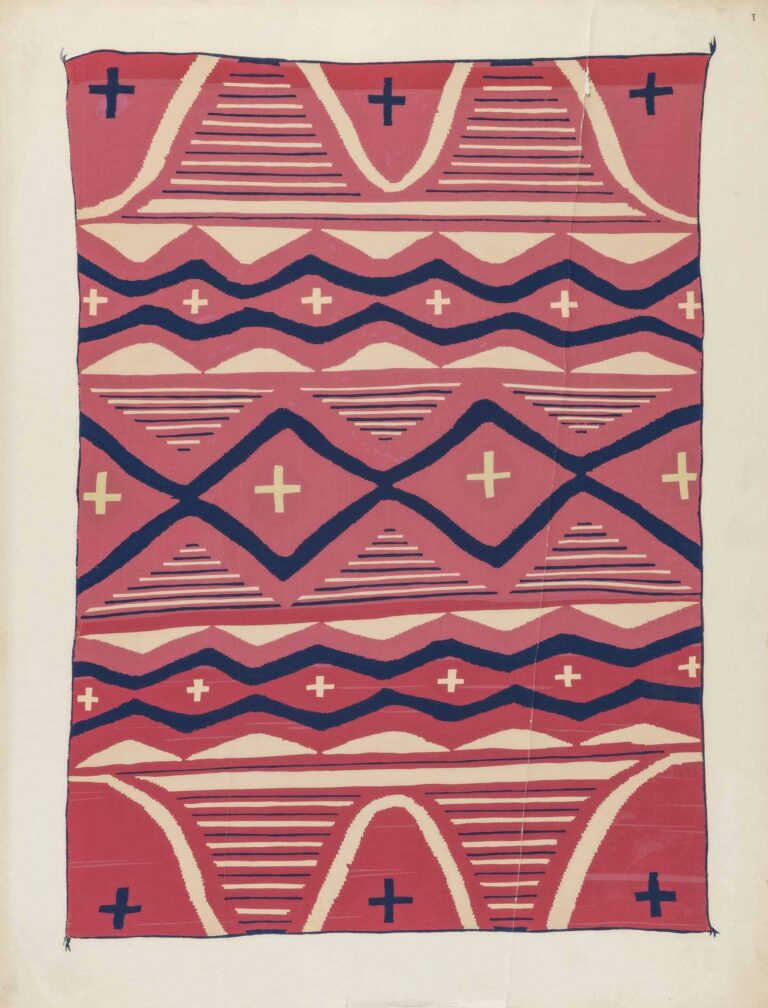

Ewing was first hired by the FAP to work as an engraver on the Portfolio of Spanish Colonial Design. He was then classified as an experimental artist1 and, as such, commissioned by the Project’s director, R. Vernon Hunter, to try new ways of working, including mosaic and silkscreen printing. His best-known contribution to the New Deal is the Navajo Blanket Portfolio, a set of fifteen silkscreen prints of Navajo weavings.

For the Portfolio project, Ewing was hired in 1939 through the FAP by the Laboratory of Anthropology (founded in 1927 by John D. Rockefeller to study the Southwest’s Indigenous cultures; the Laboratory is now part of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture) to make prints of its Navajo rug collection for distribution to the United States Indian Arts and Crafts Board “in furthering the improvement of Navajo weaving,” to “Indian service schools” for instructional purposes, and to other public educational institutions such as universities, libraries, and museums. Ewing first made paintings of the rugs and then was assisted by Eliseo Rodriguez in producing 200 prints of each painting. Silkscreen printing was such a novel technique at the time that it took the artists three days to make their first print. “We [first] made our squeegees, to move the paint across the screen, out of an auto tire because there wasn’t a squeegee invented then,” Ewing recalled. “And then we used a window-cleaning thing and that didn’t work because the oil melted the rubber.”2 Finally, they partnered with a local manufacturer to design and produce equipment that worked.3 Only ten of the original fifteen prints have survived in Gallup’s collection, but the National Gallery of Art has a complete set.

Ewing credits the New Deal with helping to launch his career, saying it offered “a wonderful chance, from getting out of art school to make a transition to professional, and besides making it possible to eat,”4 and adding that “I could break away from the WPA [Works Progress Administration] and have my own business.”5

Indeed, he continued as a prolific serigrapher for the next four decades, producing silkscreened posters for the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial from 1939 to at least 19716 and receiving numerous book commissions from major institutions across the country. Additionally, he taught at the Santa Fe Indian School in the 1940s and introduced artist Harrison Begay to silkscreen printing, a technique Begay would later translate into a successful printmaking business called Tewa Enterprises. After the New Deal, Ewing expanded his repertoire to include oil paintings, watercolor, gouache, and acrylic. He had his first solo show in 1946 at the New Mexico Museum of Art.7