Eliseo Rodriguez grew up near the now-famous artistic enclave of Canyon Road in Santa Fe, NM. As a teenager, he delivered firewood and did odd jobs for Canyon Road residents—scholars, artists, writers, and patrons who made up the town’s “Anglo intelligentsia.”1 It was there he first met Józef Bakoś and other members of “Los Cinco Pintores.”

At the age of fifteen, Rodriguez was granted a two-year scholarship to the Santa Fe Art School, where he was admitted as the “only Spanish.”2 There, his teachers included Bakoś.

In 1935, Rodriguez married his wife, Paula. They built a house and lived the rest of their life close to where Rodriguez was born.

Rodriguez was hired by the Federal Art Project (FAP) in 1936: “When I took my craft work, paintings on glass, carvings and tinwork, in for sale . . . the store manager told me she couldn’t buy any more items, but maybe I should go meet Russell Vernon Hunter [State Director of the Federal Art Project for New Mexico],” Rodriguez recalled in a 2003 interview. Hunter instructed him to apply for relief at the county courthouse to prove eligibility for the FAP. “[After being approved] I went back to Mr. Hunter. He gave me all kinds of materials to work with, canvas, paint, watercolors, everything. I was excited and felt like I was in business.”3

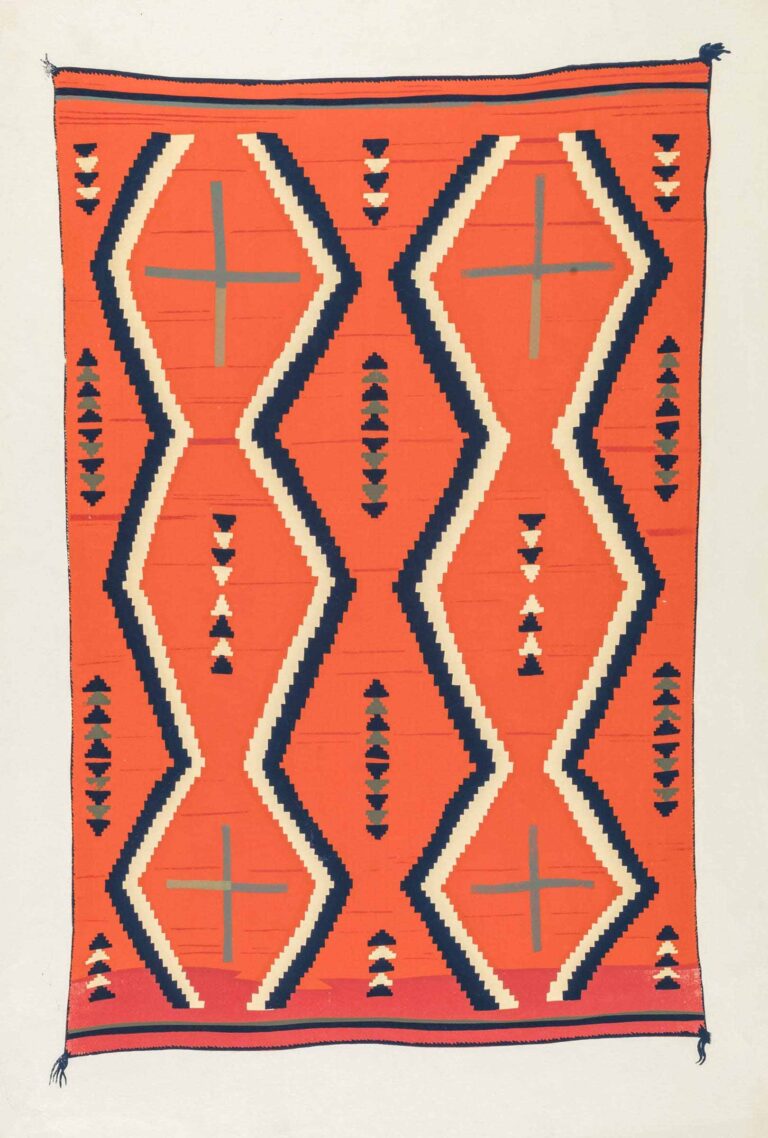

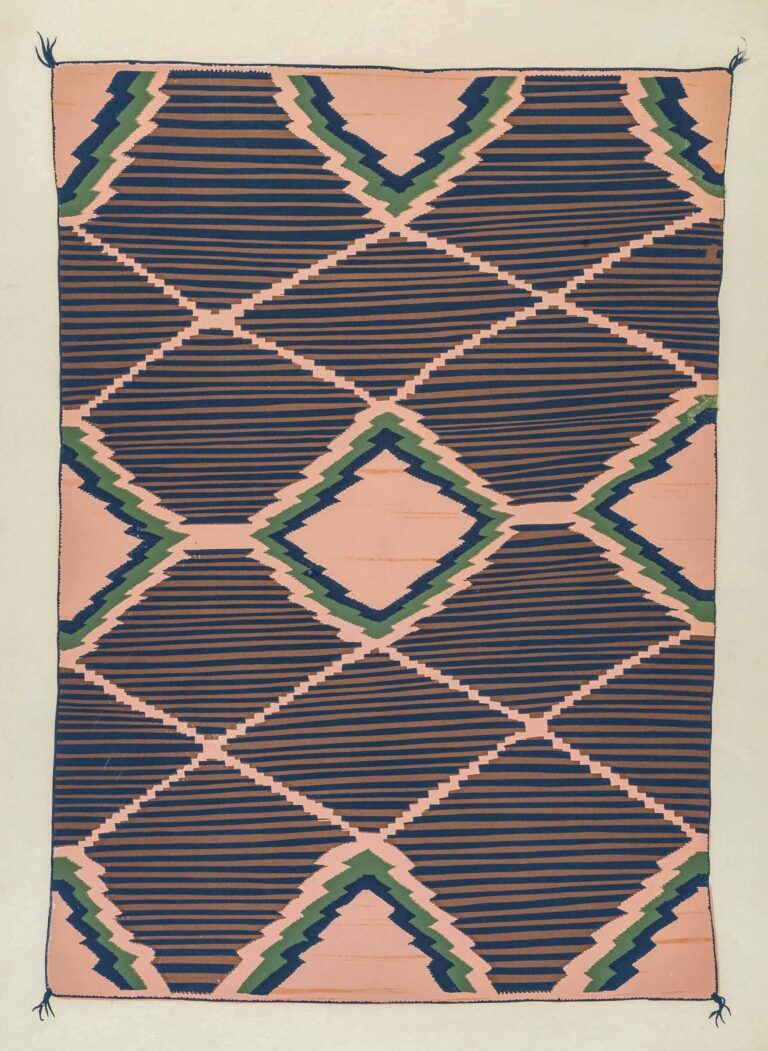

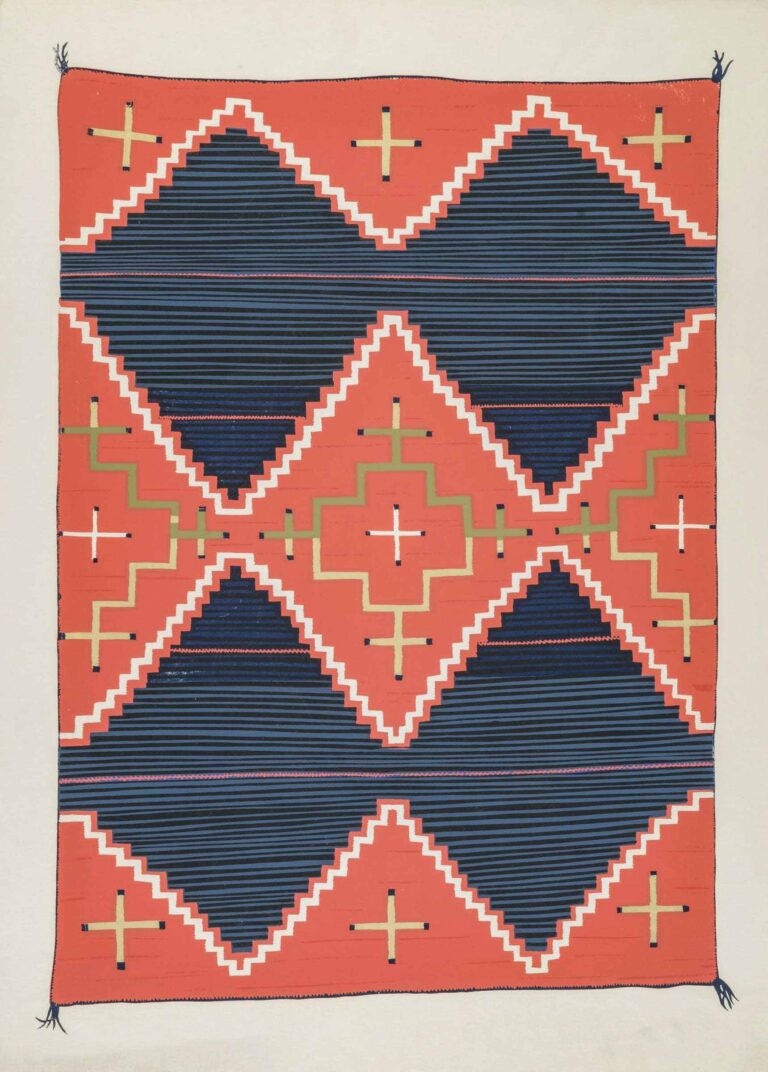

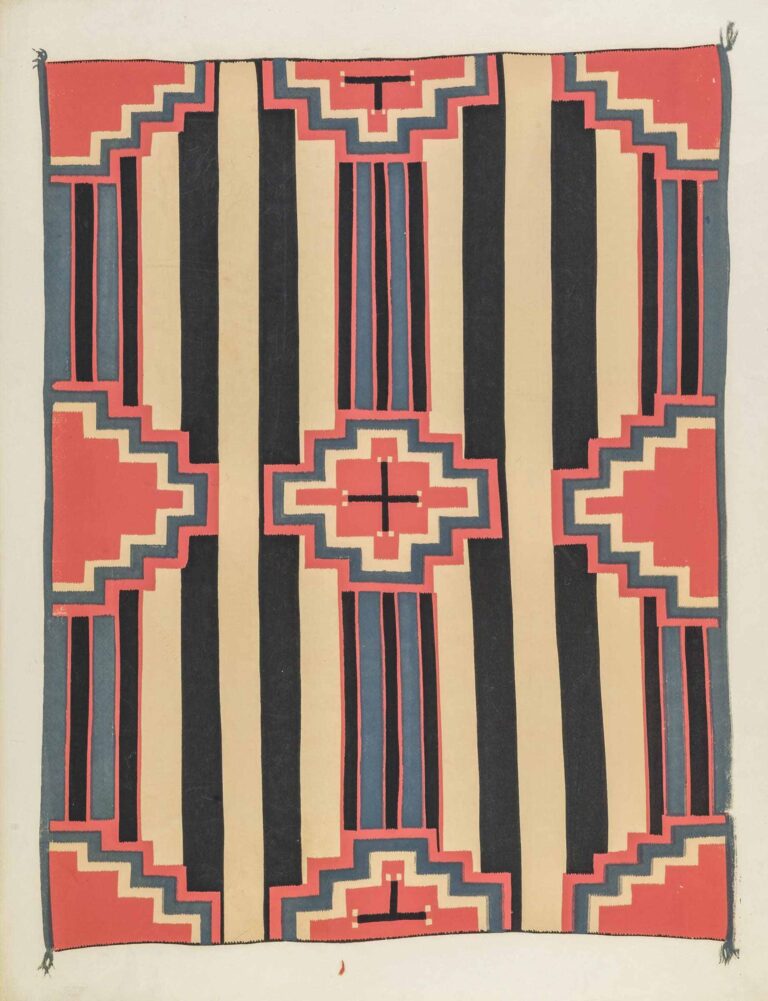

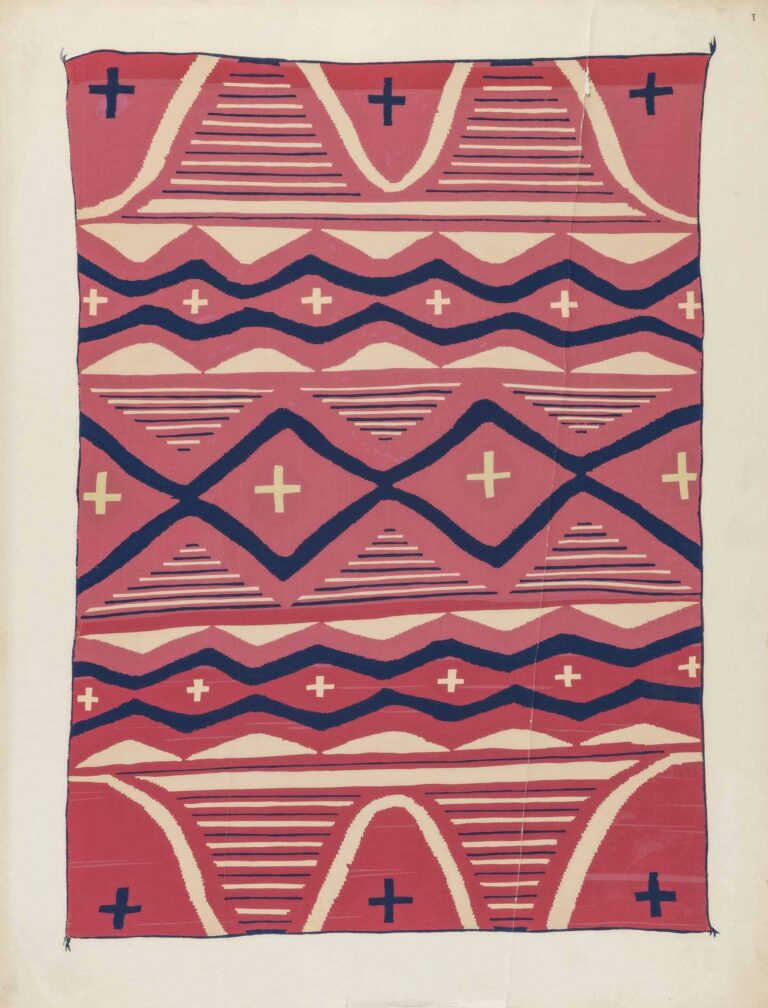

Rodriguez contributed to the FAP in a variety of ways—he was, in his words, “always willing to do anything I was asked to do. I was willing to be versatile.”4 Over the course of his employment with the FAP, Rodriguez helped Paul Lantz complete a mural for the Texas Centennial. He also helped friend, neighbor, and colleague Louie Ewing apply the silkscreen printmaking technique to create a portfolio of Navajo rug designs for the Laboratory of Anthropology (founded in 1927 by John D. Rockefeller to study the Southwest’s Indigenous cultures; the Laboratory is now part of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture). Additionally, he hand-colored prints for the Portfolio of Spanish Colonial Design. Rodriquez also painted in reverse on glass and created oil-on-canvas paintings for the FAP.

“[I made] $75 a month. We were paid by the month and since we didn’t have a family yet that took care of our grocery needs for a month. You turned in your work once or twice a week or once or twice a month depending on how fast you worked.”5

Rodriguez was one of the few highly regarded Hispano artists working for the FAP. “There weren’t a whole lot of Spanish people working in the Project . . . We weren’t just assistants. Although in some cases, we were considered helpers.”6 The Museum of New Mexico Art Gallery (now the New Mexico Museum of Art) first exhibited his work in 1936, and by 1938, “his paintings also hung alongside works by his teachers and other recognized Anglo artists, including . . . Sheldon Parsons.”7

E. Boyd, who supervised the creation of the Portfolio of Spanish Colonial Design for the FAP (and who later became a curator of Spanish Colonial art at the Museum of New Mexico Art Gallery and then the Santa Fe Museum of International Folk Art), introduced Rodriguez to the straw appliqué technique. “She said that this form of straw art originated in Africa, was picked up by the Moors in Spain and brought by the Spanish to New Mexico,” said the artist. “It was tacky, messy, and tedious work . . . I was willing to try anything so I tried doing the straw inlay appliqué work and enjoyed doing it and wanted to keep it going as a form of art that was dying out.”8

By the 1950s, Eliseo and Paula Rodriguez were the last remaining practitioners of straw appliqué in New Mexico. In the 1970s, with encouragement from a conservator at the Museum of International Folk Art, they began exhibiting their work. Today, Eliseo and Paula are credited with saving and renewing the art form, which is once again thriving in New Mexico. In 2004, the National Endowment for the Arts made both artists National Heritage Fellows.

While Rodriguez is most famous as a straw appliqué artist, he was multitalented, working in a variety of media such as oil on glass, oil on canvas, watercolor, lithography, ceramics, wood, and cabinetry. Rodriguez credits the FAP with his success: “It did more for me than if I had gone to college. It gave me so many possibilities.”9